Anywhere but Here

Anywhere but Here

March 12 – April 19, 2025

1 Rivington Street, New York

Barrow Parke, Aglaé Bassens, Rodney Graham, Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds, Adam Henry, John Houck, Dana Lok, Bridget Mullen, Joan Nelson, Emily Mae Smith, Joan Snyder, Elif Uras, Dylan Vandenhoeck, Lulu Varona, Stacy Lynn Waddell, Tim Wilson

Anywhere but Here explores representations of both our interior and exterior environments, embracing landscape as a metaphor for a psychological or emotional space. The exhibition addresses how the landscape genre offers a form of escape and a necessary retreat, particularly in times of disorder and uncertainty, and espouses the ways in which quiet reflection can strengthen belief systems, embolden ideals, and generate new possibilities for world-building.

The exhibition presents new work by Barrow Parke, Aglaé Bassens, Edgar Heap of Birds, Adam Henry, John Houck, Dana Lok, Bridget Mullen, Joan Nelson, Emily Mae Smith, Elif Uras, Dylan Vandenhoeck, Lulu Varona, Stacy Lynn Waddell and Tim Wilson, as well as historic works by Rodney Graham and Joan Snyder.

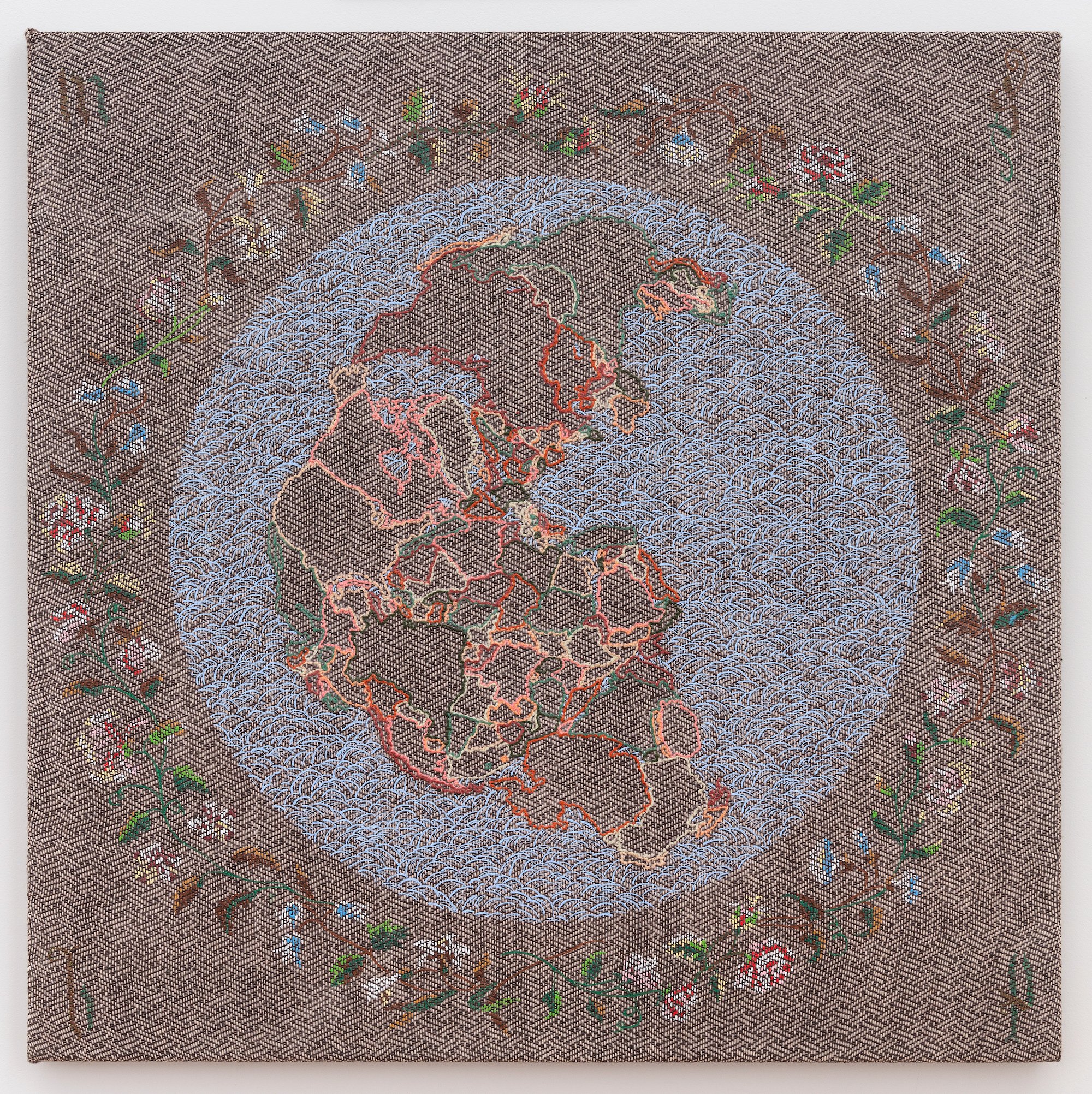

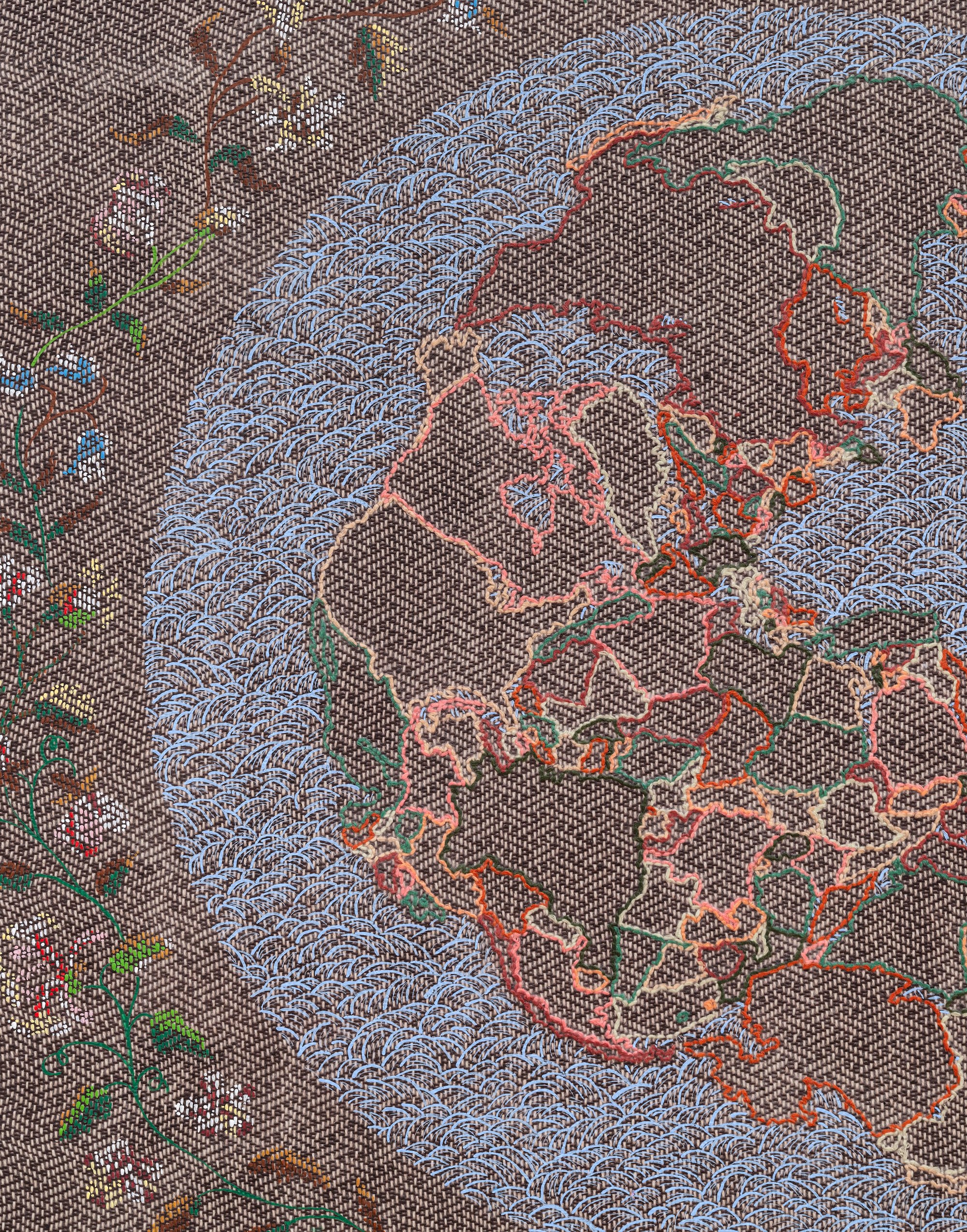

BARROW PARKE presents a new weaving, Pangaea, inspired by British embroideries of maps from the 16th to 18th centuries that depict the supercontinent Pangaea. Outlining where current country borders would be if the land mass had remained intact, the map created by Barrow Parke shows the arbitrary nature of political borders. The floral ring motif encircling the globe is a reference to the importance of plants and botany within the history of weaving. One of the oldest human technologies, weaving originated in the Neolithic era when early humans wove branches, twigs and plants into objects of utility such as baskets and shelters. The artists’ initials are inserted into the corners of the work—a nod to the traditional method of authorship on weaving samplers.

Citrus Curtain by AGLAÉ BASSENS was painted from a photo the artist took during the pandemic, walking past a window in Brooklyn and catching a glimpse of home life during a time of extreme isolation. Windows are a recurring motif in Bassens’s work, a theme she attributes to being a foreigner for much of her childhood. Through the eyes of the artist, windows are utterly ordinary, yet they represent a magical frame between the familiar and the unknown.

HOCK E AYE VI EDGAR HEAP OF BIRDS's Neuf series evokes landscape through the rich use of color, form, and a deep reverence for the natural world. The palettes are frequently inspired by his travels to diverse communities around the world that–like Heap of Birds’s own Cheyenne and Arapaho tribal nation–have been dispossessed of their land and sovereignty, yet faithfully preserve their cultures and traditions. Heap of Birds’s Neuf paintings reject the Western tradition of linear perspective to faithfully represent our experience of the world, rather, they seek a more embodied connection to our environment. Here, Heap of Birds presents a recent foray into collage, exploring his signature forms in new material.

RODNEY GRAHAM was an influential contemporary Canadian artist best known for his Conceptual work in photography. Graham humorously conflated personal and historical references with themes of nature, music, art history, and popular culture. Tree on the Former Site of Camera Obscura belongs to a series of photographs of trees taken by the artist in the 1990s. An isolated tree stands against a low horizon line, filling the center of the picture. However, the photograph is framed upside down. These “inverted trees” follow Graham’s early experiments with the camera lucida, a room-size pinhole camera that dates to ancient times. Foregrounding the mechanics of sight (that images pass through our eyes upside down, and then are corrected by the brain), Graham reminds us that no artistic representation is, in fact, “natural.”

ADAM HENRY’s recent work and artists with whom he is in conversation have been a meaningful source of inspiration for this exhibition. Well-known for his abstract paintings, which explore perception through optical play and the use of color, recent works have introduced a horizon line and a recurring form that looks like a color spectrum–developments that address the landscape genre. Henry has described the spectrum as an avatar, imagining his position from within the work and the surrounding abstractions as a possible psychological space, replete with turbulent weather formations, open skies, and parallel energetic environments.

Throughout all his work, JOHN HOUCK’s ongoing interest in psychoanalytic theories of memory and the mind permeate both subject matter and process. Houck never paints from photographic images, focusing instead on intentional acts of imagination. Various exercises in the studio—such as meditating on objects with an emotional resonance, or, invoking hypothetical landscapes from memory—are integrated into the composition of a single painting. Houck’s perceptual processes share an affinity with movements from early 20th century that similarly investigated the subconscious, among them symbolism and surrealism. In Dreamer, Houck purposefully integrates his drawing practice into the painting to create a dialogue between the rendered and the imagined.

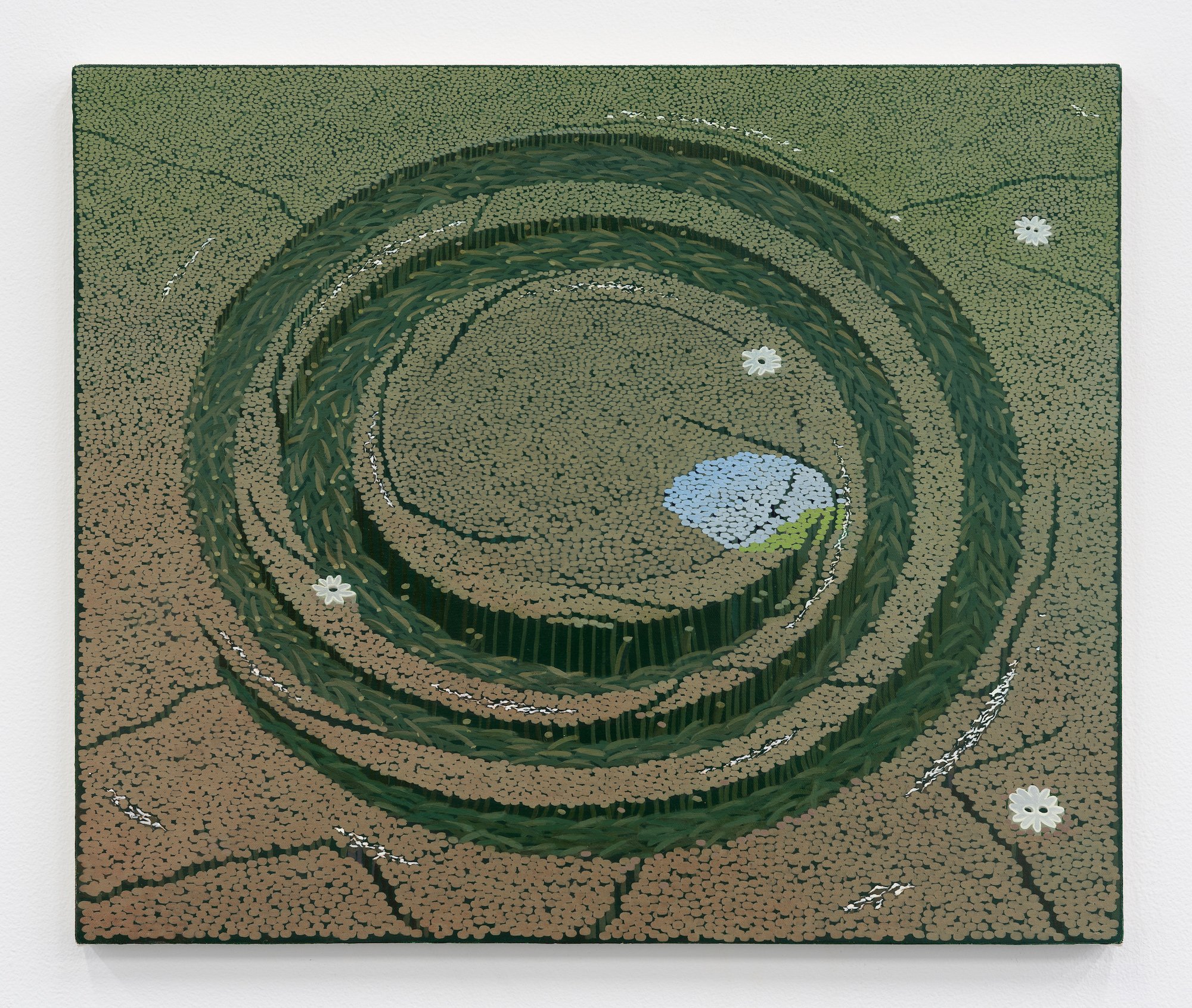

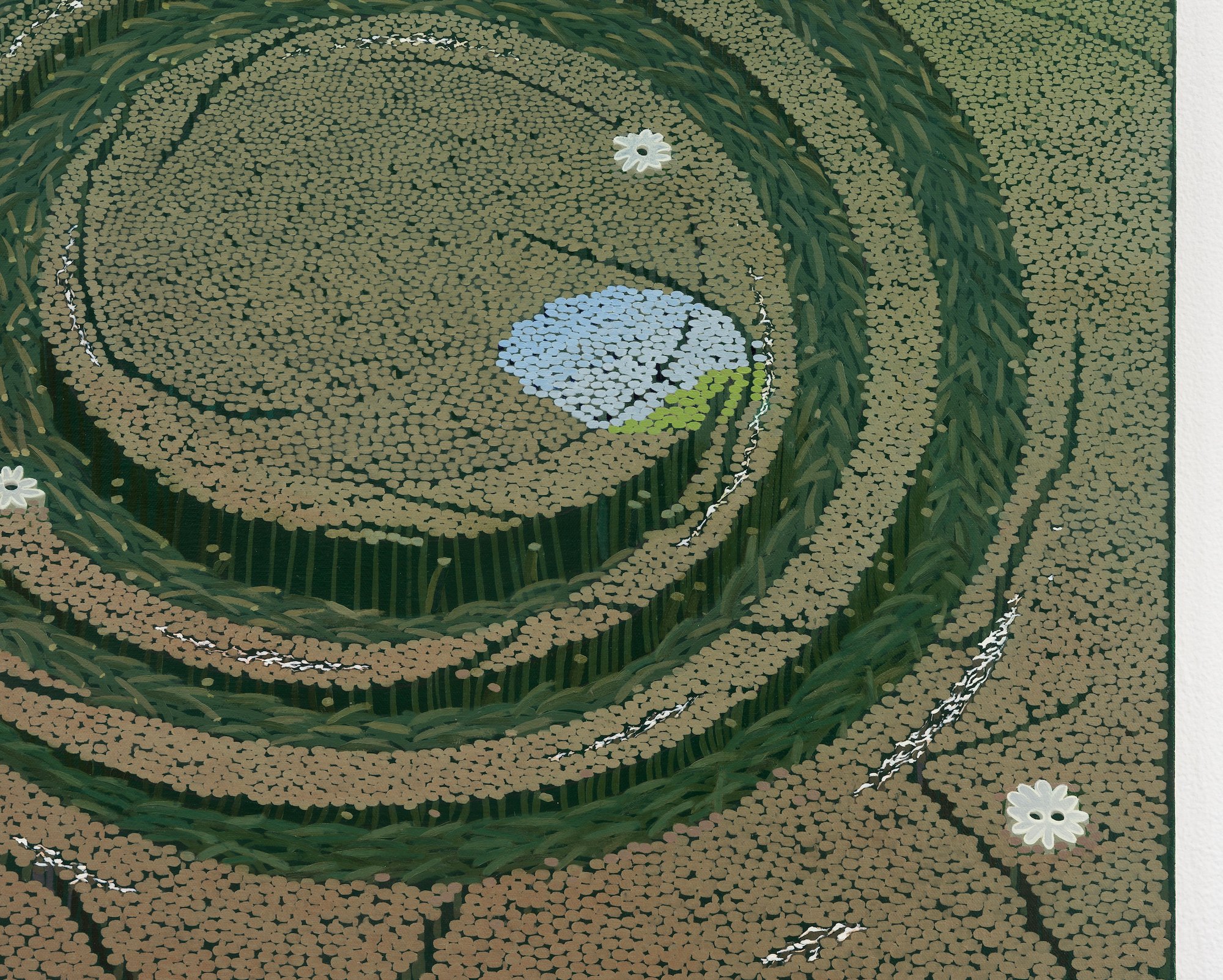

DANA LOK’s painting Path Through Tissue and Bone presents a spiral path tamped down in a field of cells or grass, a kind of hedge maze that could also be a channel in a body. The work was inspired by a 16th century game board on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, an early sample of the game Goose. Lok considers how we carve pathways of meaning though noise by repeated trampling. Stepping in one direction begins to mark a trail that another may follow. When enough feet take that trail, a feedback loop may take effect until barriers accumulate on either side of the trail and the way to go becomes clear. It's a metaphorical process that could describe feedback loops between culture, language and thought, the learning and reinforcement of cultural knowledge, or biological processes like genetic selection based on environmental constraints.

BRIDGET MULLEN’s work frequently employs a free-association process of repurposing abstract gestures as figurative elements. Distorted bodies prioritize somatic, sensory experience over language, and ambiguous, shape-shifting imagery embodies the double-sided nature of entanglement. The use of repetition gives Mullen’s compositions a sense of motion, such as in Loggy Ringerz, where repeated forms were generated using a set of rules inspired by the golden ratio. A chair, a figure, and black pipes create the appearance of receding illusionistic space. The pipes and the hands that clutch them suggest that something menacing, or possibly empowering, is afoot.

JOAN NELSON is well-known for her fantastical landscapes that evoke both the sublime and the surreal. Since the start of her career in New York in the 1980s, Nelson’s singular focus has been on the awe and the artifice of the tradition within which she is working. Nelson’s invented and appropriated images push back against a male-dominated history of the landscape painting genre and question a deeply rooted, North American vantage point centered on narratives of Western expansion, conquest, and resource extraction. Here, a fireball or comet descends, a cataclysmic event that begs the question, "What happens next?"

A few years ago, EMILY MAE SMITH began working part time upstate New York, a shift in location that imbued her paintings with greater influence from the natural world. Well known for her surreal and playful lexicon, as well as her frequent nods to art history, the most recent works fuse her signature iconography with new scenarios – such as in The Conversation – in which two rabbits confront one another, against a dramatic mountain setting. This beguiling small-scale tableau focuses the attention on narrative and exchange, suggesting the sly social and political commentary that Smith is well-known for.

JOAN SNYDER has been an important figure of American Abstract Expressionism and Feminist Art for more than 50 years. In Marcia Tucker’s essay on Snyder’s early work, “The Anatomy of a Stroke,” the late scholar writes: “Snyder’s dictum of ‘more, not less,’ the welter of visual contradiction in her work, her continued concern with making impossibilities exist in the same frame of reference, all amount to a pictorial reality which shares, in its richness, the reality of our own experience, and cannot be fully comprehended outside that context.” Tree With Black Marks, 1987–1988 is a special painting that was in the personal collection of Marcia Tucker, founder of the New Museum of Contemporary Art, until her death in 2006.

ELIF URAS's practice spans ceramics, drawing and painting, frequently referencing Ottoman history and the intricate patterns found on 16th-century pottery from Iznik, an ancient town in Anatolia famous for its tile and ceramic production. Womanhood and women's labor pervades much of Uras’s work, manifesting in curvaceous sculptured forms and narrative imagery that depicts women in various states of work, play, and rest. In Dryads, Uras decorates the surface of a stoneware vase with a frieze of figures in relief, glazed with a rich palette of color and gold luster, referencing the oak tree spirits of Greek mythology.

DYLAN VANDENHOECK presents Lichens, a new painting in oil that is culled from daily experience. Vandenhoeck’s subject matter foregrounds the embodied or subjective nature of vision, often by creating his paintings en plein air. Vandenhoeck emphasizes the importance of careful observation and the substance of everyday reality through a slow painting process that layers a profusion of color, texture, light, and shadow.

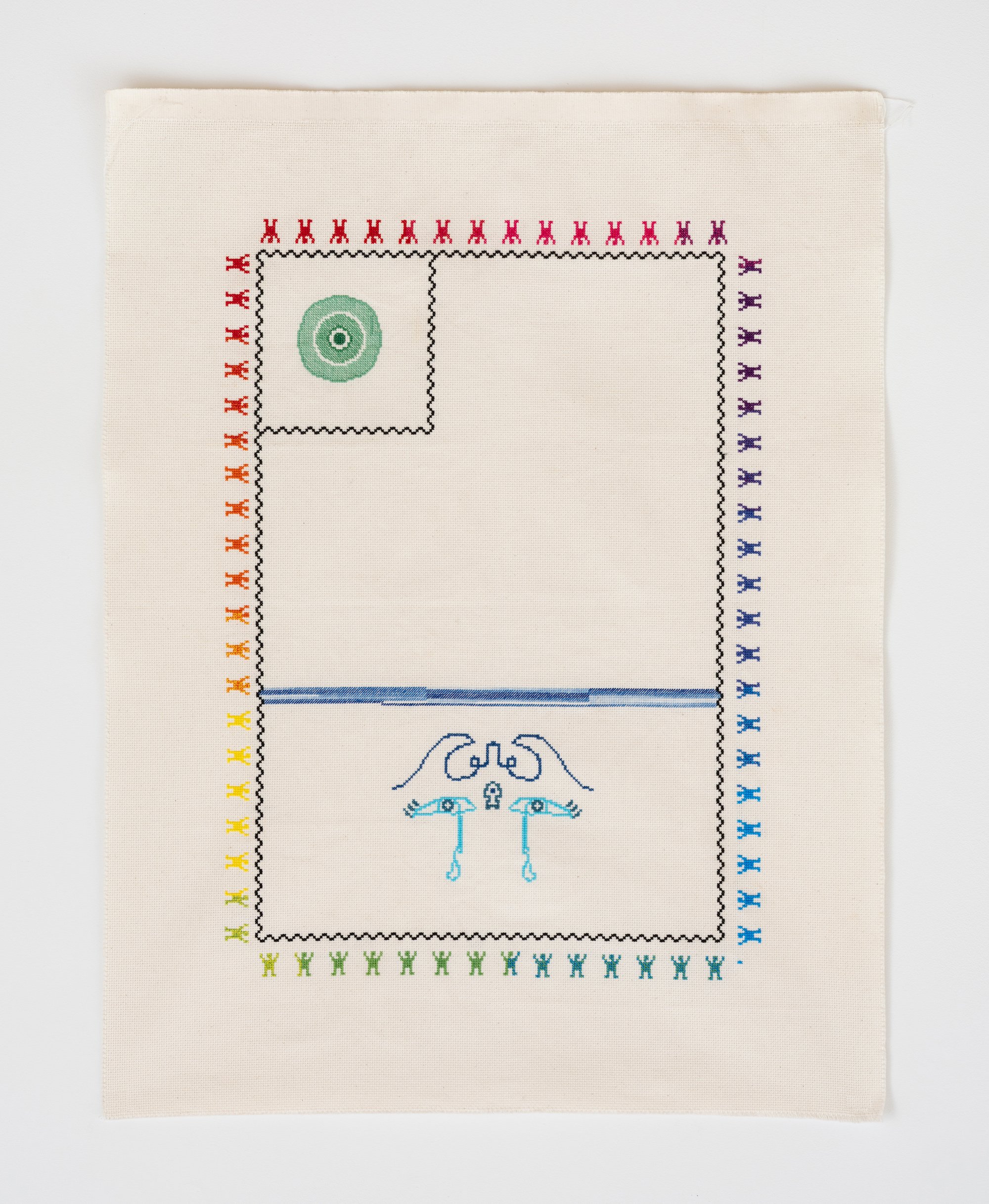

LULU VARONA's sewing practice preserves and cultivates artisanal traditions that predate US intervention in Puerto Rico. A framed border of figures is a recurring motif in her work that suggests collectivity and solidarity; and ecological themes and disasters–such as suns, landscape, water, floods, and hurricanes–often appear within her compositions, suggesting the necessity for community-oriented organizing and a respectful engagement with the environment.

STACY LYNN WADDELL’s practice investigates beauty and transformation through experimental and alchemical processes. Using heat and laser technology, accumulation, embossing, interference, and gilding, she creates works that intersect both real and imagined aspects of history and culture and pose important questions related to authorship, value, and the persuasive power of nationalistic ideology.

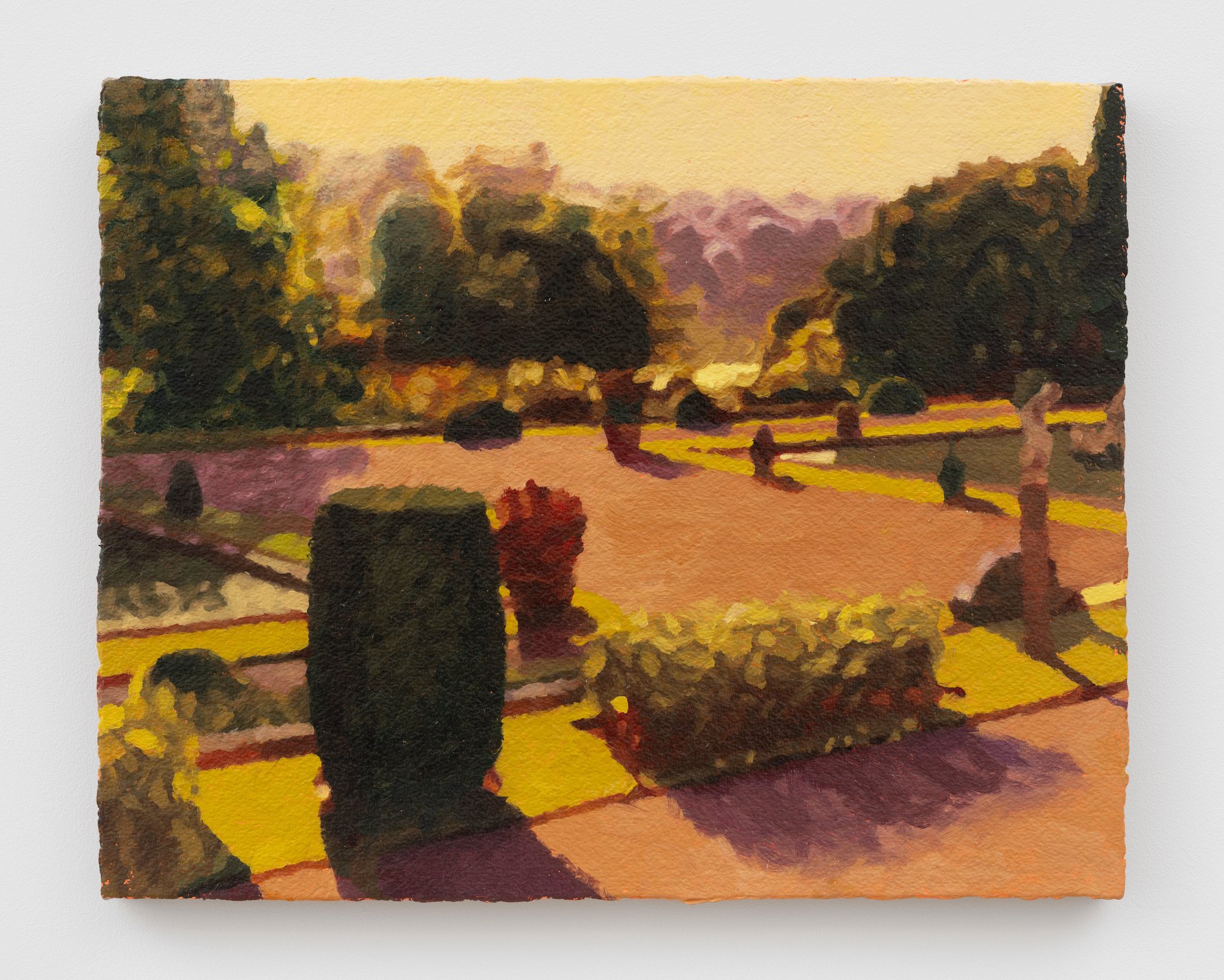

In his newest paintings, TIM WILSON incorporates French and Italian gardens, exploring how these spaces of design and desire are orchestrated for both contemplation and control. Shaped by history and human intervention, they are not nature but images of it, much like film stills or the interiors Wilson has previously painted in which artifice remains visible. In both landscape and architecture, Wilson is drawn to the way structure holds, but never dictates the scene.

—